Bishopstoke History Society

The Great War Remembered

(Produced from a presentation compiled by Chris Humby in October 2014)

This article will explore what it was like to live in the area during the period of WWI, and illustrate the operations at Hazeley Camp, Twyford, Eastleigh Clearing Hospital, the U.S.N.A.F. base in Wide Lane and work undertaken by the Carriage Works in Bishopstoke Road. This part of Hampshire, close to the English Channel, was at the forefront of activity during WWI, supporting the transfer of troops, equipment, and supplies to the Battlefields of France and Belgium. At the time when Britain and her allies had entered The Great War it was considered that the conflict would be over in a few months. It was firmly believed that it would be “The War to end All Wars”.

This Memorial at Riverside in Bishopstoke stands testament to men from our village who lost their lives during this conflict. To-day many of these individuals are only distant names in family archives. A number of family descendants still live in the area and fortunately a few have photographs and memories that they have been willing to share with us. We thought that we would try and find out some background behind the names that appear on our war memorial. Some of the men have not been traceable, although most have been identified through census and military service records. It is believed that there could be some errors on this memorial, and possibly in our research. Further research will be needed to verify our current findings. A copy of this research will be included in the appendices at the end of this article for you to peruse.

The men named on this memorial lived in Hamilton Road, Guest Road, Portal Road, Spring Lane, Montague Terrace, Church Road, St Mary’s Road, Nelson Road, Stoke Common Road and Middle Street. These were most of the roads that existed in Bishopstoke at that time. Some of you will be wondering where Middle Street is? In the Manorial days, Bishopstoke was far larger than it is to-day and included Fair Oak, Lower Upham, Horton Heath, Crowd Hill, and Lake. The road we call Fair Oak Road was previously known as Middle Street as it ran through the middle of the Manor. Even in 1911 people were still entering the old road name on their census declaration. It is intended to discuss the details for every individual on this list in this article, but we will mention one or two, as well as some of those who thankfully survived. A fuller outline can be viewed in the appendices at the end of this story.

Sidney Frank Osborn died in Flanders, France on the 28th of June 1916. He had been born in Lymington, Hampshire and was living at 143 High Street, Eastleigh, in 1911 with his wife and young family before moving to Bishopstoke. He is pictured at family weddings in Bishopstoke. He was 33 when he died. Unfortunately, his name has been miss-spelt on our War Memorial, an “e” has been added at the end of his surname. Many thanks to his family for providing this information.

Herbert John (Jack) Franklin was born in Spring Lane, Bishopstoke, in 1897. By 1911 the family had moved to 20 Guest Road. He served during The Great War with the 5th Hampshire Regiment in India. He was an old man when he died. His death was reported in The Eastleigh Weekly News in 1982 under the headline: “Man 84 dies in Collision” – “An elderly pedestrian died after he was in collision with a motor cycle at the junction of High Street & Blenheim Road.” this was where the back door of the Swan Centre is today. Like so many that served their country in the Great War, the memory of Jack’s contribution has faded, as has the memory of his brother Alfred. Alfred pictured third from left in the back row of this family portrait has his name engraved on Bishopstoke War Memorial. He is also remembered in a ledger produced by the London & South Western Railway Company. This book lists all L. & S.W.R. employees who were “Killed in Action or who Died of Wounds or Illness” during the Great War (a copy of this ledger will be included in the appendices). He was killed in an accident in India on the 6th of September 1915, aged only 20. He was also serving with his brother in the 5th Hampshire Regiment. The only details his family were given in their grief was that he fell from a balcony.

The Cousens family were well known in Stoke Common in the early 1900s. Leonard Basil Cousens (known as Basil) enlisted in the 5th Hants Regiment on 9th November 1915. He was discharged at Exeter on 13th June 1916 (aged 19) due to sickness. He is pictured in a family group with his mother Selina and sisters Lil, Rose, Eva, Florence, and Elsie.

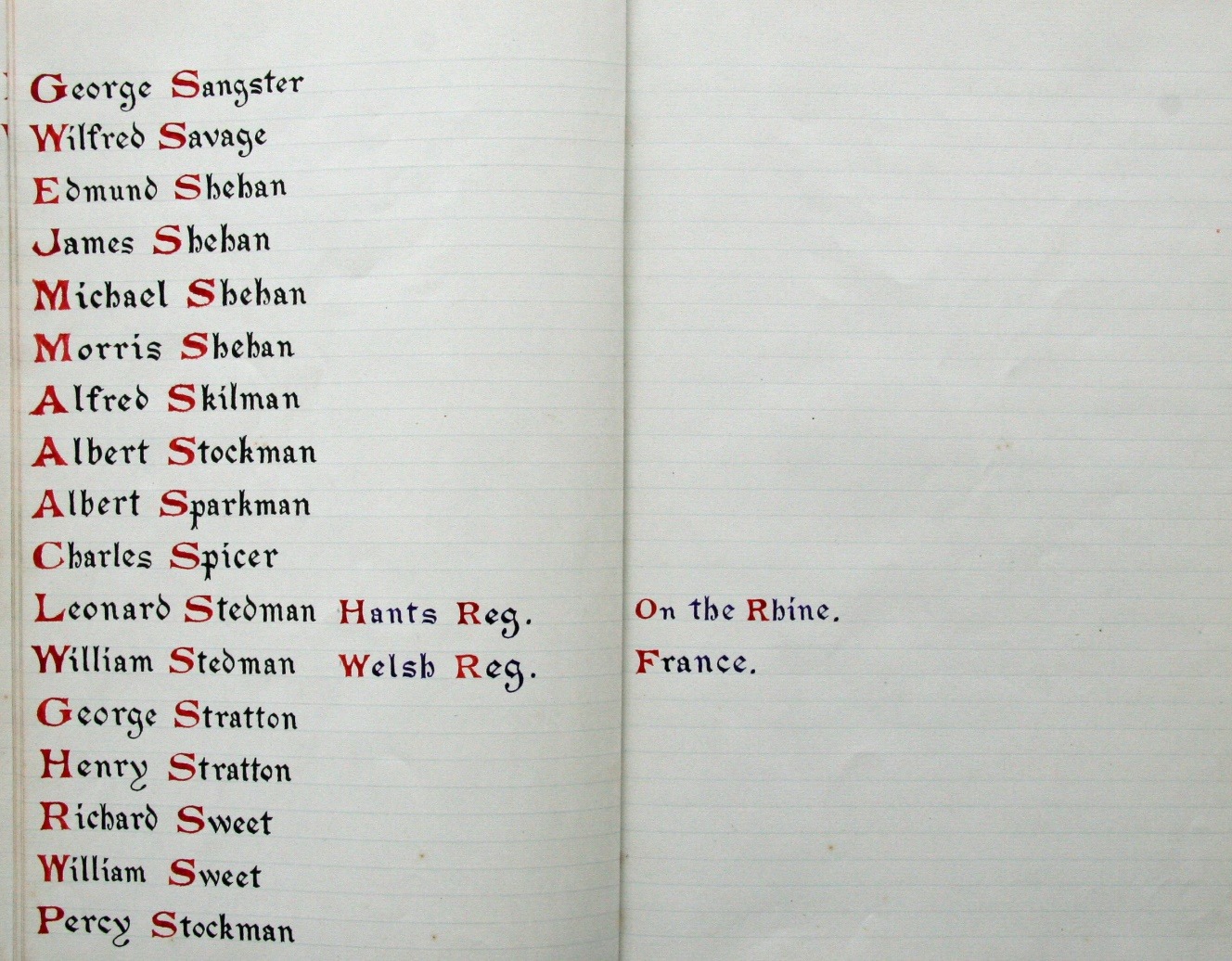

The Shehan family from 71 Stoke Common Road had a miraculous tale to tell. Originally from Ireland, the family lived in a two bedroom cottage for 50 years where they raised 12 children, 6 girls and 6 boys. Five of the boys served in the army during the Great War. Thankfully, all survived and returned home safely.

The conflict known as the Great War had commenced on the 28th of July 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany on August 4th. . My Grandfather, Frederick Charles Humby was discharged as a soldier on 14th August 1914 due to age, only 10 days after war was declared. He is pictured, next to the bass drum, holding a clarinet at Droxford in this picture from 1904.

Not wanting to accept his good fortune, he re-joined the Hampshire Regiment on 3rd February 1915 (when he was 52 years old) and was sent to France in September 1915. The Regiment was then transferred to Salonika in November 1915. He was finally discharged on 22nd June 1919 at the age of 56.

This little book must have been produced in vast quantities, probably millions of copies were distributed. It is titled “Active Service Testament 1914 – 1915”. It became known as the Lord Roberts Bible. Lord Robert’s message to the troops was “I ask you to put your faith in God. He will watch over you. You will find in this little Book guidance when you are in health, compassion when you are in sickness, and strength when you are in adversity. My grandfather sent this bible home to his family. A man of fewer words, his message to my father was simply “search the scriptures”.

He sent souvenirs home from Belgium, Egypt, Salonika, Naples, and Malta. On March the 1st 1917 he wrote a soldiers will: – “In the event of my death I give the whole of my property and effects to my wife Ada C Humby 66 (now 82) Spring Lane, Bishopstoke, Hants. Signed Frederick Charles Humby, 22nd Rifle Brigade. He was wounded and hospitalised in Malta before being shipped back to England. He was not wounded in action. Whilst stationed in the Balkans there was a lull in hostilities, and he took the opportunity to visit an old farmer and his wife who supplied food to the troops. Whilst he was visiting them, the farm was attacked by brigands (bandits) who silently killed the farmer and his wife. They also over-powered my grandfather and slit his throat. In their haste they did not cut sufficiently deep and when they had left, he was able to discharge his rifle. The rifle shot attracted the attention of a British patrol. Ironically the fact that he was wounded and shipped to Malta may have contributed to his survival. Towards the end of the war there was a major flu pandemic which swept through Europe and the Balkans and eventually the rest of the World. This pandemic was responsible for the death of over 20 million people. More people were killed between1918 and 1920 from influenza than had died in action during the whole of The Great War.

My uncle, Frederick Lionel Humby, was born in Bishopstoke in 1898 and joined the Royal Naval Air Squadron in August 1917 at the age of 18. He was stationed at Felixstowe. Life in the early days of the Air Squadron must have been rather precarious. Planes were towed behind Destroyers and used for reconnaissance. Crew had to ditch in the sea and hope to be picked up by their mother ship. My Uncle, I was told by my father, was assigned to North Sea convoy duty to Russia. These were the days before the Royal Air Force was formed and flying was under Army or Navy control. Senior officers of the period had concluded that parachutes were not to be issued to flying personnel because such a device would encourage aircrew to put their own safety ahead of their duty. There was also a practical consideration, as in those days, parachutes had to be attached to an anchor line for opening. This line would not have opened the chute when a stricken plane fell from the sky. The page to the left shows a sketch from my uncle’s notebook outlining details of the plane that can be seen in the bottom picture, whilst the page to the right contains caricature sketches of camp personnel and anecdotes relating to service life. He was not a gifted artist.

The badges on this slide belonged to my uncle (pictured left in the photo’s). They must be some of the first badges that were issued in what is still the colours of the R.A.F. today. My uncle survived the war, although my father believed that some of the trauma’s my uncle experienced during this time changed his personality. He suffered a breakdown in the 1920s and was committed for the rest of his life to Knowle Psychiatric Hospital, Fareham, until his death in 1988. I only refer to this because very little is mentioned about what effect stress had on those that served in the Great War. They were simply expected to “get on with it” and be grateful that they had survived. It is only in recent years that mental trauma associated with military conflict has been recognised and treated more compassionately.

The advent of war brought about social change. The mistress of the Bishopstoke Infants School, Miss Ethel Preece, became Mrs. Ethel Croft in April 1914, when she married Charles Harold Croft, Headmaster of Bishopstoke Boy’s School (pictured centre). They were married in St Mary’s Church opposite the school in Church Road. The Hampshire Education Committee, in July 1914, ruled that, Mrs. Croft, as a married woman, could no longer be permitted to retain her position as mistress of Bishopstoke Infants School and she was given notice to quit. Married women were not permitted to be teachers. The decision to dismiss Mrs Croft was reviewed in October 1914. The committee decided that married mistresses would, because of projected teacher shortages, be allowed to remain in office for the duration of the war. A legacy from these times is that lady teachers are traditionally, even today, still called Miss, regardless of their age or marital status.

School certificates were issued to celebrate Empire Day in 1916 and were awarded to children who had sent some comfort to troops serving in the Great War. These particular certificates were issued to my mother, who lived in Romsey. She was awarded a certificate for providing an Xmas food parcel for the troops serving abroad in the same year. This would have been a significant family sacrifice as her father, a civilian, had been killed in an accident in Fordingbridge, in November 1916, and her mother was left without means of support and six children to raise. These certificate reflect how ordinary families put their own difficulties aside to give some comfort to our troops.

It is perhaps also important to show what Bishopstoke looked like during the period of the Great War. This building would have been a major landmark in the village. This is Bishopstoke Mill. Bishopstoke Mill was located at the junction of Riverside and Bishopstoke Road. It was 70 feet long and 27 feet wide and as you can see, far larger than the small building that commemorates the site today.

Shops were also needed to support the growing population and the newly developed roads to the south of the village became known as “New Bishopstoke”. This scene showing Bishopstoke shopping centre is recognisable today and the picture was probably taken in 1916 or 1917. How do I know this? Well, the young lad at the front of the group on the pathway is my father and he was born in 1909. I would guess that he is about 7 years old in this picture. Notice the mud road and gas lighting. It may surprise you to learn that electric street lighting did not start to appear in Bishopstoke until the 1950s.

Riverside has changed a little from when this picture was taken in the early 1900s. The people in the picture are standing in front of the old Post Office and next door is the barn which belonged to the Anchor Inn. The barn has been replaced by the new doctor’s surgery, whilst the Anchor Inn building, whilst still standing, is now converted into flats. Notice the absence of railing along the side of the river. Horses probably had more sense than humans to avoid falling into the river.

This picture of Spring Lane is perhaps the most striking image of how different life in Bishopstoke was around 1914. The new Post Office on the right was built in 1906, and the building is still there today. The Methodist church, next to the Post Office was known as “The Tin Chapel. It was demolished in the 1950s and has been replaced by the Fish & Chip Shop and convenience store. Beyond the chapel the old house has been demolished and replaced with Bishopstoke Working Men’s Club. Beyond is Palmer’s Bakery. This shop is now a hairdressers, and what was the bake house at the rear, is Spring Hill Car Repairs.

All the cottages on the left have been demolished and replaced with flats. There is still a shop on the corner of Hamilton Road, but it is now a hairdressers, not the sweet shop that it was all those years ago.

This picture was taken at the junction of Spring Lane and Hamilton Road and national flags can be seen festooned across the road. This picture may show how the village was decorated to celebrate the end of hostilities in 1918. What is sobering is to realise just how much has changed during the last 100 years or so.

Not far from Bishopstoke, in the village of Twyford, men from London were being prepared to go to war. In 1915 The Ministry for War first commandeered farming land, owned by the Best family, at Hazeley Down.

Work began to build a massive wooden military complex to house the young ‘Pals Regiments’ from London on their way to the docks at Southampton to join the Allied armies in France. It took eleven months to build this military transit camp on a 105 acre site. Facilities included water, electricity, more than five miles of roads, huts to accommodate up to 6,510 troops and stabling for 1,718 horses.

There were 408 huts and water consumption per day was in the order of 95,000 gallons. This raises two questions:

How do you feed such a large body of men?

What impact did such a large group have on the local population?

These are questions to which we do not have answers.

Four and a half miles of supply pipes were laid to provide water and a further three and a half miles of drainage constructed. As you can see from these pictures, weather was not always conducive to trench work, but such conditions were good preparation for future challenges that the men would encounter across the Channel in Europe.

Recreation for the troops at Hazeley was supported by the Young Men’s Christian Association.

Hazeley Down Camp became home to the 14thBattalion (London Scottish), 15th Battalion (Prince of Wales Own Civil Service Rifles), 16thBattalion (Queen’s Westminster Rifles), 17thBattalion (Poplar & Stepney Rifles), 20th Battalion, (Queen’s Royal West Kent), the Royal Garrison Artillery, The Tank Corps, and representing the British Commonwealth, Canada’s Royal Newfoundland Regiment. The London Regiment, known as Princess Louise’s Kensington’s, Welsh Regiments, and Portuguese troops were also stationed at Hazeley for a period.

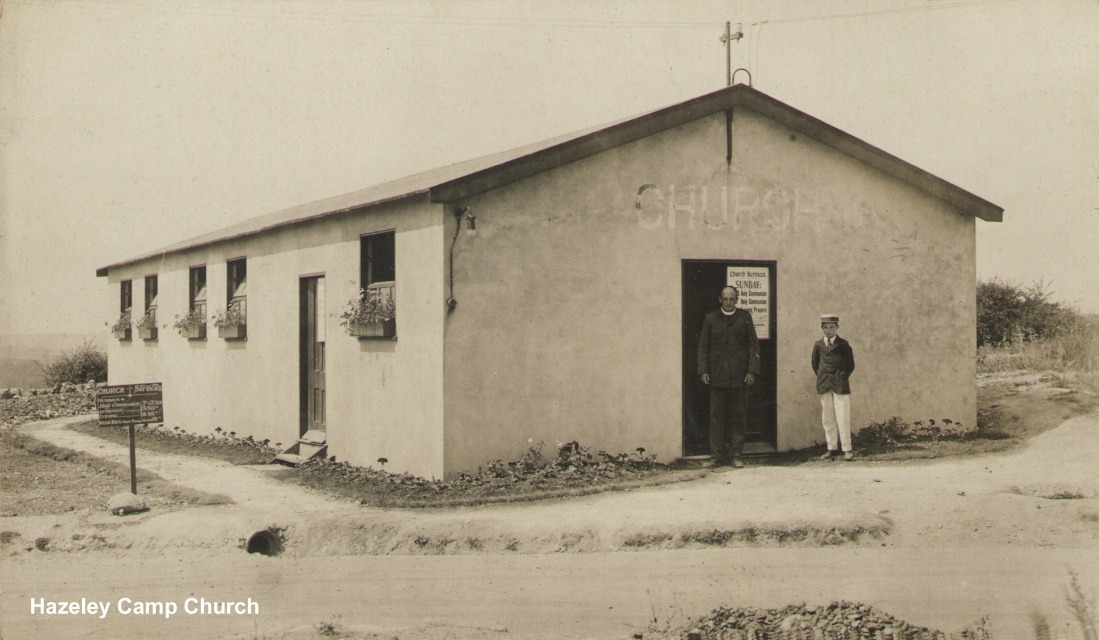

Pastoral support was part of a soldier’s preparation for the conflict to come, although this church was somewhat small for such a large congregation.

The Altar from the church was designed to be portable and could be used in an outdoor environment as the next pictures illustrate.

This is an outdoor service and the Altar from the previous picture is now being used in front of an assembled Regiment.

This picture shows just how large a body of men could be assembled at any time, and it is probable that this was a service to bless those that were about to depart to the front line in Europe.

Imagine the spectacle as, on completion of this service, vast khaki columns of men marched from Hazeley Down into Twyford en route to France and the battles to come.

It is sobering to consider how many of these eager assembled young men survived or were traumatised by the events they were about to face. It is also sobering to consider just how traumatised young men from London must have felt when they found themselves stationed in the fields, in what must have seemed like the back and beyond in the rural Hampshire village of Twyford.

The following is a poem called “Hazely Down Camp.” and reflects how lads from “The Smoke” adapted to life during their stay in Hampshire. The author is unknown. Lines from this poem will be interspersed with more pictures of Hazeley Camp.

There is an isolated, desolated spot I’d like to mention.

Where all you hear is “Stand at Ease,” “Slope Arms,” “Quick March,” “Attention.”

It’s miles away from anywhere, by gad, it is a rum un,

A chap lived here for fifty years and never saw a woman.

There are lots of little huts, all dotted here and there,

For those that have to live inside, I’ve offered many a prayer,

Inside the huts there’s RATS as big as any nanny goat,

Last night a soldier saw one trying on his overcoat.

It’s sludge up to the eyebrows, you get it in your ears,

But into it you’ve got to go, without a sign of fear,

And when you’ve had a bath of sludge, you just set to and groom,

And get cleaned up for the next parade, or else, it’s “Orderly Room”.

Week in, Week out, from morn till night, with full pack and a rifle,

Like Jack and Jill, you climb the hills, of course that’s just a trifle,

“Slope Arms,” “Fix Bayonets,” then “Present,” they fairly put you through it,

And as you stagger to your hut, the Sergeant shouts “Jump to it”.

With tunics, boots, and puttees off, you quickly get the habit,

You gallop up and down the hills just like a blooming rabbit,

“Heads backward bend,” “Arms upward stretch,” “Heels raise,” then “Ranks change places,”

And later on, they make you put your kneecaps where your face is.

Now when this war is over and we’ve captured Kaiser Billy,

To shoot him would be merciful and absolutely silly,

Just send him down to Hazeley Down, there among the Rats and Clay,

And I’ll bet he won’t be long before he droops and fades away.

Clearly there was also excitement to be had in the grand metropolis of Twyford as this picture shows of soldiers revelling in the facilities at Twyford Parish Hall.

Whilst the bustling Twyford High Street reflects life as it once was. Notice the sign outside the Phoenix Inn advertising that it is a Lady Cyclists House. I suspect that the soldiers at Hazeley Camp would have displayed similar welcoming signage, but probably without any takers.

The village constable, who can be seen standing in the centre of the High Street, would have been on hand to ensure that there was no trouble.

And in nearby Queen Street it is unlikely that any dalliance would have gone unnoticed by neighbours, or the young boy lurking furtively behind the tree.

This picture shows a couple of soldiers in Hazeley Road, Twyford, heading towards the village for an evening of socialising in the local pub.

Apparently, the Bugle Inn was a popular watering hole for the troops from Hazeley Camp and some of them can be seen in this picture. I have been informed that the normal practice at closing time was for those that were able to do so, to walk back to camp. Those that were incapacitated, were thoughtfully arranged by the Landlord around the base of the tree that can be seen on the right of this picture, with the help of a wheelbarrow. There was a standing arrangement that a wagon from the camp would arrive shortly after closing time to collect the “not so empties” and return them to the tender care of the Sergeant Major, where they would be tucked up warm and cosy for the night. As our next picture illustrates.

The sad reality for the soldiers stationed here, was that Hazeley in rural Twyford, was an alien environment in comparison to the urban background they were used to. Hazeley as a training camp was also an environment far removed from the conditions that they would soon be facing. This card was sent home by a Welsh soldier, from Twyford, in July 1917. The opening sentence being:” Just to let you know I am still alive.”

When training had been completed, soldiers from Hazeley camp had to be transported to the front in France. This was via Southampton docks. The lucky ones were route marched to Shawford railway station and taken to Southampton by rail. Many more were route marched all the way to Southampton. They would not have been aware that of the six million men from the UK who had been conscripted to fight, over 750,000 would be killed and around two million would be wounded.

The London and South Western Railway workshops in Bishopstoke Road constructed many hospital trains and thousands of stretchers and red cross accessories for the war effort.

This booklet illustrates some of the work undertaken in the Eastleigh Carriage Works and shows in detail how hospital trains were designed and used in the repatriation of wounded personnel. Some of the ambulance trains were based in Europe, whilst others were used to transport troops throughout the UK to specialist military hospitals and clearing hospitals that had been set up specifically for the duration of the war. There were 16 carriages in each ambulance train.

This particular series of photographs relates to an ambulance train that was built for the American Army, for use in France and was completed at Eastleigh Carriage and Wagon Works in April 1918. The train was painted khaki-green, with the Red Cross initials featuring prominently on each side of the vehicle.

Officers were given special privileges when only lightly wounded, as this picture of the officer’s staff dining car illustrates. The dining compartment was located immediately behind the kitchen, thus ensuring that their food would be served piping hot.

Officers were also given privileged accommodation in the sick officer’s car away from the rank and file, if they were not unduly injured.

The infectious cases car at the front of the train accommodated 24 beds and was separated from the rest of the train by an airtight partition. The 2nd car was the staff car with living accommodation for the medical staff.

This is a picture of a ward car, prepared for lying down cases. Each ambulance train could accommodate 418 persons in this configuration.

If bottom beds in wards were converted into seats, as shown in this picture, then 680 patients could be accommodated. The beds were also designed to be used as stretchers. Also included in the specification for ward cars were fixed and portable fans which were particularly helpful for patients who had been “gassed”. Perhaps not so helpful was the provision of ash trays.

Hygiene was an important element of the design. The interior of the carriages had a clinical white enamel surface. The beds were also hinged so they could be raised for cleaning, as shown in this picture. These pictures were taken for promotional purpose. Reality is that wounded servicemen being repatriated, due to necessity, were often subject to squalid and less than ideal hygienic conditions on ambulance trains.

The Kitchen Car contained the linen store, pantry, and cook’s quarters as well as the kitchen itself with kitchen a cooking range and another stove which could heat large quantities of water for washing and cleaning.

This is a picture of the Pharmacy compartment. The first portion of the Pharmacy Car was used as a ward for 12 special “bed cases”, or as an emergency waiting room. As well as the pharmacy, there was an office, emergency room, and store for medicines and medical equipment.

The last carriage in the hospital train was the Brake and Stores car used for general stores, kits, provisions, and linen. There was also a special compartment for meat storage. At the end of this carriage there were quarters for the train guard/brakeman.

Brigadier-General Hugh W. Drummond, chairman of the London and South Western Railway, reported that since the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 to the end of 1917, no less than 15,500 Ambulance trains, loaded and empty, had passed over the South Western Railway system.

Many of the wounded soldiers that returned to the UK were transferred to clearing hospitals. Patients rarely stayed in a clearing hospital for more than a few days before being relocated to other facilities, given home leave and/or returned to combat. There were a number of facilities in the area, Netley Hospital was a large military hospital for the seriously wounded, as was Haslar at Gosport, and a major operation existed at Andover where there was a large military presence. There was a small clearing hospital at Hazely Camp to handle up to 100 patients and in Eastleigh, Chamberlayne Road Boys School was commandeered for use as the Eastleigh Clearing Hospital and was opened in April 1915. It became a successful military hospital and casualty clearing station under the command of Colonel Twiss. These facilities were later extended, and huts were constructed in the Leigh Road Recreation Ground to meet additional accommodation.

It is clear in these pictures how the transformation from school to hospital was achieved. Conditions at home would have been infinitely better than conditions in field hospitals abroad. Many of the men would also have been keen to make contact with their families. My grandfather, who I mentioned earlier, was shipped back to England to Southampton where he was to be transferred to a clearing hospital at Salisbury. Being near to home, he “somehow” got separated from his unit in Southampton Docks and in his confusion, mistakenly boarded the wrong train, and found himself at Eastleigh Railway Station without a ticket. The ticket collector, who he had been at school with, refused to let him pass, so according to family history, he “decked” the ticket collector and went home to see his family, before making his way to the hospital in Salisbury.

There do not appear to be any records remaining of the Military Clearing Hospital in Eastleigh. It is believed that what records remained were destroyed by bombing in London during WWII.

This colour wash picture postcard shows that patients were issued with pale blue uniforms, to distinguish them from active personnel. There was a practical reason for this. When soldiers returned from the front, they were wearing their battle-worn uniforms, which were probably torn, muddy, bloodied, and harbouring lice or ticks. This was not the image that the government wished to be seen by the British public.

Although in black & white, there is a clear distinction between patients and serving soldiers in this picture. The chap standing in the middle of the picture is an orderly and he does not look as if he is going to take any nonsense from any of the patients. This chap is wearing a red cross badge on his arm which would indicate that he is a first aider. In all the pictures that we have of Eastleigh Clearing Hospital, there are no images of any female nurses. There are many pictures showing men with the red cross arm badge, and it may well be that as the patients at Eastleigh were mainly walking wounded, perhaps it was considered better to maintain discipline rather than the need for specialist nursing care. This picture also illustrates how the canvas sides of the huts could be opened to permit maximum ventilation.

The picture to the left shows mealtime in what had been the playground of Chamberlayne Road Boy’s School, with about 160 men seated at trestle tables. The picture to the right shows a kitchen that had been erected in the school playground. Question is, where did they eat when it rained? There may have been facilities available in the main body of the old school. The school hall would have been the obvious choice, but as we have already seen, that had been converted into a hospital ward. It is also quite feasible that other facilities in Eastleigh were commandeered. There were a number of suitable buildings such as churches, drill halls, and the nearby town hall where a mess hall could have been established for large numbers of people. There were also facilities in temporary accommodation in the base in Leigh Road recreation ground, alternatively, they could have simply used their huts.

This is a picture taken inside the Clearing Hospital kitchen in Chamberlayne Road.

How many thousands of men spent time in Eastleigh before moving on will never be known.

This picture is from the clearing hospital in Eastleigh. The orderlies and patients were prepared to pose for this picture, yet there is an atmosphere of trauma or apprehension, particularly in the eyes of the patients, or perhaps it is just me being over sensitive.

This picture demonstrates how close to the residents this hospital was. There must have been considerable interaction between wounded soldiers and the people of Eastleigh.

This picture shows the huts in Leigh Road Recreation Ground. You can imagine how large an operation the clearing hospital in Eastleigh became.

Apparently during WWI young lads from the area would try to befriend walking wounded at the hospital and, in return for a tunic button or cap badge, they would invite them home for tea. Don’t know what their mums thought of this arrangement! This picture shows the badges and buttons collected by Ern Honeybone from Bishopstoke which he still treasured many years later. Thanks to his family for sharing this information with us.

It is believed that, eventually, there was a capacity for nearly 1,300 beds to accommodate wounded personnel In Eastleigh, with orderly accommodation being provided separately at the Railway Institute in Upper Market Street.

This is a proposed plan of the accommodation for Eastleigh Clearing Hospital in the Leigh Road Recreation Ground. This map shows that washrooms and toilets were to be provided at either end of the camp. To the east, there were 19 bathrooms, separate washrooms and separate toilets with a cubicle capacity of 29. To the west, next to the Council Offices, accommodation was to comprise 16 baths, more washrooms and toilets with cubicle capacity of a further 26. At the centre of the camp there was to be a kitchen, near to the bandstand. Sadly, there are no plans for the accommodation in Chamberlayne Road.

This photograph shows the huts in the Recreation Ground nearest to the Railway Institute. There is a small group of people assembled at the end of the path in Leigh Road. This is close to where the “Railwayman Statue” stands today. The bathrooms, washrooms and toilets mentioned earlier can be seen as the longer building to the right of picture. In the far distance, on the right, where the car park now stands adjacent to Romsey Road, there is a large building, which was the social club, provided by the Y.M.C.A.

These pictures show men, all with red cross emblems, assembled for group photo’s either outside Chamberlayne Road Boy’s School, the Railway Institute, or at the Council Offices in Leigh Road. These would have been the Orderlies responsible for patients at the Eastleigh Clearing Hospital.

It would appear that these men were also military musicians, and it is presumed that these are the orderlies that were responsible for patient discipline and wellbeing.

This group photograph was taken to commemorate the staff who served at Eastleigh Clearing Hospital towards the end of hostilities. There are a few patients in the picture as well. The picture appears to have been taken in the playground of Chamberlayne Road Boy’s School.

A celebratory event was hosted by Colonel Twiss, in appreciation of the staff at Eastleigh at the end of hostilities. This picture was probably taken in the Railway Institute building which had accommodated the orderlies, many of whom can be seen in the picture.

Behind the Railway Institute were recreational facilities provided by the Young Men’s Christian Association to support the patients and staff at the clearing hospital and this is a picture of the interior. The Y.M.C.A. is a charitable institution and provided welfare facilities at home and overseas for troops during WWI. The Eastleigh operation, because of the transient nature of the hospital is most likely to have provided refreshments, books, newspapers and somewhere for able soldiers to relax and socialise. Elsewhere in the UK the Y.M.C.A. provided sleeping accommodation for soldiers in transit or on leave, whilst overseas they provided refreshments close to the front for battle weary troops and provided support for family members visiting dangerously ill men. This picture is from a postcard that was sent from Eastleigh Clearing Hospital on 28th August 1916 to an address in Hastings. It mentions that the soldier arrived at Eastleigh on Saturday and would be sent to Brighton on Wednesday.

This postcard was franked and over stamped with The Clearing Hospital, Eastleigh, in red, presumably by the censor. Somebody, perhaps the censor has overwritten in pencil, “He has only hurt a finger.”

Patients from Eastleigh Clearing Hospital can be seen at Barton Mill, enjoying some fresh air. This scene is not so recognisable to-day. It was taken in Bishopstoke Road, where the housing association offices now stand, opposite Chickenhall Road roundabout. Barton Road can be just seen on the right of picture and the large house on the left is Barton Farmhouse, which later became Barton Peveril School. To-day this is where the G.W. Martin factory is located.

A major feature of Eastleigh, before and during WWI was the recreation ground at the end of Dutton Lane, which had been built by the L.& S.W.R. for employees of the carriage works and the people of Eastleigh. In its heyday it boasted one of the finest banked cycle tracks in the country as well as football pitches, cricket pitches, a running track, seated sports pavilion, and changing rooms. In this picture patients from the clearing hospital can be seen assisting the start of a bicycle race.

Patients from the clearing hospital watching a lady’s bicycle race. It is believed that the race was intended to be won by the slowest contestant around the course without them touching the ground or riding in a backward direction.

Entertainment was important to maintain moral amongst troops and Eastleigh Variety Theatre in Market Street became a very popular venue for patients, as these pictures show. This was in the day’s way before television. Films would also be shown, but they were black and white silent movies. Live entertainment was very popular although the quality of the artists and the standard of performance was often variable and the style of entertainment a lot different to what we expect today. The picture in the centre is of the artistes Chic & Chum who were duettists and dancers and are typical of the type of act that would have been seen at the time, although probably they were not the headline act. I will leave it to your own judgement whether this duo was of the calibre that would make it to the final of “Britain’s Got Talent” nowadays.

Eastleigh is a town that was built to accommodate workers of the London & South Western Railway. The railway station that opened in 1839 was built to serve Bishopstoke, however, the arrival of the carriage works in 1890 led to industrialisation and more housing was needed to accommodate railway workers than Bishopstoke could support at the time, so housing was built in Eastleigh instead and the town began to develop with shops and banks to support the new population. Forty years after the arrival of the railway, in 1881 the population of Eastleigh had grown to about 1,000. By 1891, with the influx of workers to the carriage works, the population of Eastleigh increased to about 3,600, and increased to over 7,600 only 10 years later. The arrival of the railway locomotive works in 1910 further increased the population in Eastleigh to around 13,000, which is about what the population was at the start of the Great War. The clearing hospital, with an influx of 1,300 patients and additional staffing would have had a significant impact on the towns population. In this picture from around 1913 the appearance of Leigh Road opposite the railway station is reminiscent of a frontier town.

With a significant increase in population due to the railway, the town of Eastleigh was able to accommodate larger shops like Bakers on the corner of Leigh Road and Market Street, and Eagle Buildings in Leigh Road. This is how the town looked in 1914. Today this is part of Leigh Road is the pedestrian precinct. In Leigh Road, next to Baker’s on the corner of Market Street at no 17 was Collins the butchers, followed by E & H Rowe, drapers, at no’s 19 & 21 (this shop became Woolworths in 1931). At no 23 was Boots the Chemists, whilst next door, just out of picture at no 25 was Home & Colonial Stores Ltd who were grocers. These are the shops that people living in Eastleigh would have been familiar with during 1914-1918.

On the corner of Leigh Road and Southampton Road, Prismalls the grocers at no’s 34 & 36 were replaced by the Union of London & Smith’s Bank Ltd, around 1914. Next door at No 38 was Budd’s the butchers, whilst Henry Baker ran dining rooms at no’s 40 & 42.

The Junction Hotel, on the 20th of July 1918, became home for a few weeks to Lieutenant-Commander George de Chevalier, an early U.S. Navy aviation pioneer who established an operational United States Naval Airforce base at Wide Lane for the repair and assembly of aeroplanes. He journeyed to the Wide Lane airfield each day; on his journey he would have passed.

The Locomotive Works which were opened in 1910. This building still stands today and is one of the features of Eastleigh that is as familiar to people now as it was one hundred years ago.

What would not be so familiar to people a hundred years ago are the operations that now take place in the railway workshops, nor would they understand how few employees now work there compared to the thousands in its heyday.

Scenes like this in the running sheds, the other side of Campbell Road from the Locomotive Works are just a long forgotten train spotters dream yet this would have been a familiar scene to people in the early 1900s. A number of men from Eastleigh and Bishopstoke who worked for the railway lost their lives serving in the Great War. Of 1,494 London and South Western Railway employees who served in the armed forces during WWI, 116 were killed. Eastleigh lost 52 railway employees. Casualties from Eastleigh accounted for nearly half the total of the L. & S.W.R. employees who died in military service during the Great War. (A copy of a ledger by the London and South Western Railway relating to service by railway staff during WWI is included in appendices at the end of this article).

In 1914, the junction of Southampton Road and Market Street looked like this and although there were very few motor vehicles in those days, the sign in front of the Eastleigh Hotel warns motorists of danger and advises that they should proceed at 5 mph and, with caution. Today, you may still proceed past this point at about 5 miles per hour, mainly because you are stuck in rush hour traffic. The Eastleigh Hotel building still exists although it has now been converted into flats. Market Street is no longer accessible from Southampton Road, as it was when this picture was taken. Access was blocked some time in the 1970s.

This picture shows Southampton Road with the Eastleigh Hotel just visible in the far distance. Opposite these houses was farmland. The fields were flat and level and had been formed by many years of alluvial deposits from the River Itchen. Perfect conditions for use by early aviation pioneers.

Edwin Rowland Moon was pictured with his Moonbeam 2 in the meadows of North Stoneham Farm in 1910. The brand new Eastleigh Locomotive Works and the houses in Campbell Road can be seen in the background. Edwin Moon had an involvement in the family business, the Moonbeam Engineering Company Ltd in Town Quay, Southampton, which gave him the opportunity to indulge in his passion for aeroplanes and automobiles. He joined the Royal Naval Air Service in 1914 and on promotion to Flight Lieutenant, was stationed at Felixstowe where he was assigned to North Sea patrols. In 1916 Lt. Moon was posted to East Africa where he became a prisoner of war.

(Pictures courtesy of Peter New – The Solent Sky)

(Pictures courtesy of Peter New – The Solent Sky)

After he was repatriated, Edwin Moon became a Squadron Leader in the R.A.F. (The R.N.A.S. and R.F.C. being disbanded when the RAF was formed on the 1st of April 1918) and he became Commanding Officer of the flying boat station at Felixstowe. It had puzzled me why young men from Bishopstoke, seen in an earlier picture, had opted to join the R.N.A.S. In researching for this article, it is believed that, as impressionable young men, there was an element of hero worship of a well known, local aviation pioneer which influenced their choice of the R.N.A.S. Major Moon had had close encounters with death on more than one occasion but sadly in April 1920, whilst on a routine training flight from Felixstowe in a flying boat, with him at the controls, the plane spun into the sea from a height of 1,700 feet and four of the crew, including Moon, were drowned. Although probably not the first person to land an aeroplane on the meadows of North Stoneham Farm, Edwin Moon, who periodically used these fields for flying according to Peter New, may well be considered as the founder of Eastleigh Airfield. He must have been amazed at the developments that took place in 1918 when Eastleigh Aerodrome became the largest United States Naval Airforce Base constructed in Europe during the Great War.

This airfield at Wide Lane was originally being developed as an aircraft acceptance base for the Royal Flying Corps. When the United States entered WW I, the U.S.N.A.F. formed a Northern Bombing group in France. The sites that they had already established for the repair and maintenance of aircraft had come to the attention of the German Air Force, so the Americans sought permission to establish a suitable site in the U.K. that would be out of range of German bombers, but within flying distance of the front line bombing squadrons. The R.F.C. already had another airfield for repair and maintenance of aircraft, which was operating from a site further west in fields belonging to Nutbeem Farm. The 2nd R.F.C. base in Wide Lane, Eastleigh, was offered as a viable location and included some hangers which were already under construction. This enabled operations to proceed rapidly.

Parts of the U.S. airfield were named after their serving senior officers. The selection of personnel and equipment for the Northern Bombing Group that the Eastleigh airfield was built to support, was under the direction of Lieut.-Commander Benjamin Briscoe. The flying field was named after him. His chief aide was Lieutenant C.A. Tinker, the approach to the new arrivals and departure Hall at Southampton International Airport still carries the name “Tinker Ally”. What had been steady progress under the British, accelerated at a rapid pace under American management. The first commanding officer and driving force behind the establishment of the Eastleigh airfield, Lt.-Commander George de C. Chevalier, had a reputation for getting things done. Within four weeks the base was operational, and 4000 officers and men were installed in tents and huts alongside the railway line. The main road into the airfield that ran parallel with the railway was named Chevalier Avenue in his honour. (Today it is called Mitchell Way). Chevalier, his job done, was replaced as commanding officer, within eight weeks, by Commander Bayer T. Bulmer in September 1918. Bulmer’s background had been in engineering as factory manager and superintendent of repair work at the Charlestown Navy Yard in Boston.

The view bottom left shows tents that had been donated by the British Red Cross as temporary accommodation. The United States Navy Public Works Department built 25 barracks in only 30 days as well as constructing a galley, and mess hall. Some of the accommodation to the south of the airfield can be seen in the picture bottom right. Many of the buildings they constructed were still standing in the 1960s.

Facilities at Eastleigh Aerodrome included a bank for U.S. Navy personnel. The Captain of the Pay Corps was E.W. Bonnaffon, Bonnaffon Boulevard was named after him. The new brick galley, pictured top right, sufficient to serve 4000 men, was built in 150 hours. The barrack accommodation mentioned earlier can be seen in greater detail in the picture bottom right. Remember, these huts were completed at an average of about one per day, whilst all the other building work was being undertaken. The senior officers would have been grateful to the Red Cross for providing tents to accommodate so many personnel at such short notice. The servicemen would have been eternally grateful to get out of the tents into more substantial accommodation, particularly with the onset of winter in the damp and cold British climate.

The steel framed mess hall, in Sims Circus, was constructed in 130 hours, a permanent Y.M.C.A. for the recreation and entertainment of the men was created on Rue De La Hanrahan, ready for use in 180 hours. Heavy bombers were shipped across the Atlantic to Southampton and then by road to the aerodrome for assembly. Once tested they were ferried to France, flights taking about 90 minutes. The Book, “Battle of Eastleigh” contains a number of poems written by the men that were stationed here. Food was clearly an important element of life at Eastleigh Airfield. This example illustrates memories of the “Chow” Line, which can be seen in the picture, bottom left.

“I’ve heard of centre rushes

And of rushes through the line,

Of rushes for the subway,

And the rush to get the dime,

But every rush that ever rushed,

Must sure and certain bow,

before that rush – that screaming rush –

The awful rush to chow!”

This picture depicts DH 9A’s at Eastleigh Aerodrome ready to be flown to France by U.S.N.A.F. pilots in the late summer of 1918. There seems to have been some reluctance by American servicemen to be stationed here. A poem, “The Flying Yeoman”, reflects one ratings opinion: –

“I wonder why it was my fate

To come to Eastleigh, Hants?

I wonder if it’s not too late

To have another chance.”

This picture shows De-Havillands in the assembly and repair hanger in Eastleigh with some flight officers.

This picture shows a De-Havilland DH6 parked on Cone Concourse.

A regular visitor to the U.S.N.A.F. at Eastleigh Aerodrome was the Commanding Officer from the Royal Air Force Assembly and Repair Squadron based in Leigh Road. Apparently, he would regularly fly over in his Sopwith Averil Pup to say hello. He would sometimes do a bit of showing off with some aerobatics. The Americans christened him, “The Flighty British Major”.

This is a picture of the assembly and repair department with flight officers at Eastleigh in 1918 at Wide Lane.

It was not all work and no play, and it was important to balance the pressure of war and being away from home with entertainment, when appropriate. This picture, titled “A little Jazz on Chevalier Circle” shows the U.S.N. band departing from the usual military themed arrangements to entertain the base by giving a jazz concert. It has been observed that some of the uniforms may be French. It does not look as if they are enjoying it. Something perhaps lost in translation!!!

The band sometimes provided unintended entertainment and are often depicted in “ Battle of Eastleigh” in a slightly derisory manner We have already seen a couple of poems about feelings of the servicemen, the next picture illustrates the self-effacing humour of the period.

This cartoon seems to be questioning the “quality” of musicianship and the ability to march in step. The addition of the barking dog just adds to the general ambience of din. I am sure that the dog is supposed to be depicted as barking or howling, not sniffing, as some of you may have been imagining!!!

In the book – “Battle of Eastleigh” written by the men who were stationed here, there is a tribute to the local people that entertained not only the officers, but also the enlisted men. Many people are mentioned in the book, but most notable was the support provided by the Swaythling family. South Stoneham House, the residence of Lord and Lady Swaythling, was near the airfield and each week three groups of between 20 to 40 enlisted men were entertained for tea, while two to four officers from the station were their guests at dinner three nights each week.

South Stoneham House must have appeared a little out of context with the more spartan huts and tents of the Wide Lane airfield, particularly to enlisted men from cities like New York, Boston, Detroit, Washington, and Chicago. The social structure of English society, compared to back home, must also have seemed most peculiar to the American servicemen.

This picture gives some idea of the scale of the Wide Lane operations, which with over 4,000 personnel, must have had a marked effect on the town of Eastleigh. It was the largest U.S.N.A.F. base in Europe during WWI. The U.S. Navy took command under Lt Commander George de Chevalier on the 20th of July 1918. It had been erected in record time and was operational in less than four weeks. It was the largest and most successful project ever undertaken by the U.S.N.A.F. during WWI, yet it was only operational for about four months. The Eastleigh operation was not without its casualties. A flight officer, Lt Kenneth Macleish, failed to return from delivering a plane to France, and one officer and twenty enlisted men died from illness whilst stationed at Eastleigh. The operation at Eastleigh was delivered by team work, endeavour and sheer determination which must have taken its toll on those that served. This extract from a poem titled “A Wail from Eastleigh” gives an insight.

“I’m sitting here and thinking of things we left behind,

and hate to put to paper what is running through my mind.

We’ve dug a million gravel pits and cleared ten miles of ground,

and a meaner place this side of –well, I know it can’t be found.

We’ve built a hundred kitchens for to cook our Navy beans,

we’ve stood a million musters and cleared the camp latrines.

We’ve washed a million dishes and we’ve peeled a million spuds,

we’ve lashed a million hammocks and we’ve washed a million duds.

The number of parades we’ve stood is very hard to tell,

but we’ll not parade in heaven, for we’ve done our hitch in – Well?”

Hostilities ceased on the 11th of November 1918 when peace was declared. Between 1914 and 1918 it is believed that more than 9 million combatants, worldwide, were killed and a further 21 million wounded. This picture was taken in Southampton Road on Armistice Day and shows staff from the Fair Oak Dairy Produce Company Ltd, (where the Swan Centre is today), celebrating on the flag bedecked balcony of their premises. The Japanese flag flies alongside the Union flag, as during WWI, Japan was an ally of Britain.

On the 2nd of December 1918, less than a month after peace was declared, the U.S.N.A.F. personnel began leaving their base at Wide Lane to return home, although about 600 men were to remain to arrange removal of equipment. The ways of the military are sometimes mysterious, and the first contingent boarded a train at Eastleigh Station at 6.30 p.m. with full pomp and splendour of a military band send off, bound for Liverpool where they were to board the U.S.S. Leviathan, before sailing across the English Channel to Brest, where they took on coal before finally crossing the Atlantic to New York and then home. Seems strange to send them to Liverpool, when the port of Southampton was only a couple of miles away! In January 1919, a farewell dance was organised by the Americans who remained at Eastleigh, and the whole of one hanger was elaborately arranged for the event. There was a sixty piece orchestra, and the hanger was decorated with flags. Over 2,000 people attended including many local dignitaries from Southampton and Eastleigh.

Peace returned to Eastleigh and the clearing hospital, which for a period had dominated the Leigh Road Recreation Ground was removed, and the park returned to public use. Field guns, captured from the old enemy were erected to flank either side of the walkway in the park, as a reminder of the conflict.

But what do you do with two large, abandoned airfields? The R.A.F. airfield by 1925 became the site of the Pirelli General Cable Works. The U.S.N.A.F. aerodrome in Wide Lane now operates as Southampton International Airport. Commercial flying operations did not start until the 1930s, so what became of the site in the interim?

The hangers and buildings vacated by the U.S.N.A.F. became a hostel called Atlantic Park. This hostel was created to house refugees from mainly Eastern Europe who were facing persecution in their own countries, due to political, religious, and economic instability in the aftermath of the war. Atlantic Park opened in the spring of 1922. The Park was formed as a joint venture between companies such as Cunard, White Star and Canadian Pacific Railways. It became a self-contained township with its own school, medical centre, synagogue and even a library containing books in languages such as English, Polish, Russian, German, and Yiddish.

For many, although far from luxurious, the experiences of Atlantic Park were not especially traumatic compared to the conditions that they had left behind. Although in principle residents of Atlantic Park were confined to the hostel, many freely interacted with the local community. The numbers of immigrants held at Atlantic Park slowly diminished from 1928 until its eventual closure in 1931.

(Picture from Southampton University collection)

(Picture from Southampton University collection)

The people staying at Atlantic Park were seeking passage to a new life in America. America was a politically and economically stable country and seen as a land of opportunity where people who had been disadvantaged or disillusioned with life in Europe could make a new home. Cunard, White Star and Canadian Pacific were Shipping lines with liners sailing out of Southampton bound for New York and offering passage to those who could afford it and wishing to start a new life in a new country.

The arrival in New York and the site of the Statue of Liberty was symbolic. For the U.S. personnel that had served in Eastleigh, it represented coming home. For the refugees it meant hope of a better life. Not all refugees were accepted. About 2 percent were denied admission to the U.S. and were sent back to their country of departure, despite having been granted clearance before leaving Southampton. It is recorded that some families were returned to England where they lived at Atlantic Park for 5 years or more whilst they sought a permanent place to live.

People in Bishopstoke and Eastleigh had welcomed their loved ones back from the conflict and vowed to remember those that would never return. Memorials were erected in our communities with the names of men from each town or village that lost his life, so that they would not be forgotten. In some small way, every year, we honour this commitment.

The last word should perhaps belong to those that served. In the last sentence, on the last page of the book, “Battle of Eastleigh”, the acting U.S.N. Chaplain, Lieut. Norriss L. Tibbetts in 1918 wrote on leaving England’s shores: – “This is the end of the Battle of Eastleigh, may it be the end of all battles forever.”

Sadly, this was not so.

Appendices

Bishopstoke WWI Memorial Memories

Roll of Honour

Bishopstoke

Great War – 1914 – 1918

| Albert Webb | James Owen |

| Albert Savage | Joseph Dunn |

| Albert Swete | Lionel Daventry |

| Albert Oliver | Reginald Divall |

| Alfred Franklin | Reginald Cox |

| Charles Walkley | Stephen Van |

| Edwin Finney | Samuel Jordan |

| Edgar White | Sidney Osborne |

| Edward Cox | Thomas Rumney |

| Frank South | William Poole |

| Frederick Hutchinson | William Jones |

| Frank Dann | William Baker |

| Frank Pitman | William Wren |

| George Goddard | William White |

| Herbert Pragnell | Walter Brown |

| Henry Pyle | Harry Webb |

| Harry Webb |

Bishopstoke WWI Memorial Memories

This document has been edited and produced by Chris Humby of Bishopstoke History Society, with grateful thanks to Allen Guille and Jane King for additional research. Particular gratitude is extended to Ian Taylor, a Fair Oak resident who undertook similar research of the names on that village’s War Memorials, for supporting this project and providing military insight to the campaigns and conflicts that our casualties endured.

During the course of the research into the background and circumstances behind the men named on our Memorial to the Fallen of WWI, some anomalies have been discovered. These will be explained alongside the names of those who have been remembered.

We have also established that there are others whose names could have been included on our Roll of Honour of the Great War, but for whatever reason, were not. These names have been included at the end of this document.

Whilst conducting research for this project it is my strong opinion that the naming of Bishopstoke Villagers immortalised on our Memorial, were taken at the time. It is not our role, some 100 years, later to question these decisions or interpretations. There could be many explanations of which we are not aware.

Chris Humby MSc – April 2015

Bishopstoke WWI Memorial Memories

2906/331165 Rifleman A.E. Webb – 1/8th (Isle of Wight Rifles) Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 19th April 1917.

Albert Edmund Webb lived at 154 Church Road with his parents and was a farm labourer before he enlisted in the Hampshire Regiment in February 1916. He was drafted to the 1/8th (Isle of Wight Rifles) Battalion. On 19th April 1917, at the age of 20, in the Second Battle of Gaza, his Battalion was in support of the 4th and 5th Battalions of the Norfolk Regiment in an attack on Turkish positions on the Beersheba Road, southeast of Gaza town. The attack met devastating artillery and mortar fire and of 23 Officers and 748 Other Ranks who took part on that day, 21 Officers and 546 Other Ranks were casualties. Albert Webb was one of the 248 declared killed or missing. He is buried in the Gaza War Cemetery, Palestine, where his elder brother Walter also lies.

19128 Corporal A.J. Savage – 10th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 10th August 1915.

Albert John Savage lived at 29 Hamilton Road with his parents and was employed as a gardener. He was one of the first 200,000 to answer Kitchener’s call in August 1914, when he enlisted in the Hampshire Regiment and was posted to the 10th Battalion. On 6th July 1915, the 10th Battalion embarked in the SS Transylvania for Gallipoli. Landing after dark on 6th August 1915 and with difficult advances over the next 3 days, the 10th Battalion’s positions just west of Chunuk Bair were attacked with some ferocity at dawn on 10th August 1915, by the Turks. In the confused fighting, Albert Savage, at the age of 22, was one of 155 soldiers of his battalion to lose their life. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial which stands on the tip of the Gallipoli Peninsular, Turkey.

25173 Sapper A.E. Sweet – 57th Field Company, Royal Engineers. Died 19th April 1915.

Albert Edward Sweet (not Swete as shown on the Bishopstoke Roll of Honour) was the son of William and Henrietta Sweet who lived at 4 Portal Road. He enlisted in the Royal Engineers in June 1913. In 1914, the 3rd Division, based at Tidworth and Bulford Camp, of which 57th Field Company were part, embarked with the rest of the British Expeditionary Forces from Southampton between the13th and 15th August. After marching for a week, the Division deployed on the Mons- Condé Canal, where Albert Sweet would have been employed preparing bridges for demolition. The Retreat from Mons followed, ending in the British Expeditionary Force reaching the outskirts of Paris, then to re-advance to the line of the River Aisne. In October, the Division moved north by rail to the Ypres sector. Engineers spent much time in forward trenches on the Messines Ridge to undertake repairs to damage caused by German shelling, and in some cases, mining. Albert Sweet was killed in action at Hill 60 on 19th April 1915 at the age of 22. He is buried in Wytschaete Military Cemetery, Leper (Ypres), Belgium

6136 Lance-Corporal William Oliver – 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards. Died 30th October 1914.

The roll of honour on the WWI Memorial in Bishopstoke lists an Albert Oliver. In 1911 there was an Albert James Oliver, aged 14, who was working as a Mill labourer and living at 22 Hamilton Road with his parents. There is a record of this same Albert Oliver, regimental number 552, joining the Territorials in 1912, when he volunteered for four years of service in the Hampshire Fortress Corps. In 1912 Albert Oliver’s records show that he is now living at 15 Hamilton Road and working as an engine cleaner for the London and South Western Railway. Despite extensive searches, no records have been found that show Albert James Oliver serving as a regular soldier, or of him being killed in action.

There is, however, a record of a William Oliver, from 108 Hamilton Road, who enlisted in the 1st (King’s) Dragoon Guards in 1909 and died in action during WWI. Serving at the outbreak of war in August 1914, he was immediately sent to France. After taking a distinguished part in the Battle of and Retreat from Mons, and other important engagements, he was killed in action on 30th October 1914, at the age of 24. According to records contained in the National Roll of the Great War, William had been promoted to Lance-Corporal and his next of kin, at the time of his death, are listed as living at 9 Montague Terrace. William is commemorated on the Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. It is likely that William Oliver’s name, not Albert Oliver’s, should have been included on Bishopstoke’s Roll of Honour, however, whatever the reasons, it is not our place to question nor change these decisions.

1917 Private AV Franklin – 1/5th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 6th September 1915.

Alfred Victor Franklin was a pre-War Territorial who enlisted in “F” Company, 5th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. The Regiment used the Drill Hall in Leigh Road, Eastleigh, which is now a Youth Centre. This is where Alfred probably enlisted, along with his younger brother John who were both born in Bishopstoke. His parents were living at 20 Guest Road in 1911. Alfred was employed as a cleaner on the railway and his name is included in a book which lists all London & South Western Railway employees who were “Killed in Action or who Died of Wounds or Illness” during the Great War. The Territorial Force, which Alfred and his brother John joined, was raised for home service only, but soon after the outbreak of the War many territorial soldiers were volunteering for overseas service. Together with three other Hampshire Regiment Territorial Battalions, the 1/5th sailed for India on 9th October 1914, each battalion going to a different destination. Alfred’s battalion was stationed at Allahabad where he was killed in an accident on the 6th of September 1915, aged only 20. His brother, also serving in the same Battalion, survived the war. The only information Alfred’s family were given in their grief was that he fell from a balcony. He is buried in Allahabad New Cantonment Cemetery, India.

9670 Private C.H. Walkley – 2nd Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry. Died 1st July 1916.

Charles Henry Walkley lived with his parents at 13 Montague Terrace. Before the beginning of WWI, he enlisted as a regular soldier in the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, serving with the 1st Battalion in China and Hong Kong. He was drafted to the Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, following a brief return to the U.K., when he was stationed at Hursley Park before being sent to France. The 2nd Battalion, Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry supported the 16th and 17th Battalion’s Highland Light Infantry in their attack on a feature in the German front line known as the Leipzig Redoubt, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. On this day, the 1st of July 1916, Charles Walkley was killed at the age of 33. The British Army suffered horrendous casualties, some 60,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing. It was the highest number of casualties recorded in one day of fighting in a single offensive during WWI. German dominance of No Man’s Land prevented the recovery of the dead and wounded. Charles Walkley is one of more than 72,000 names carved on the Thiepval Memorial in France, to the Missing of the Somme.

2nd Lieutenant E. N Finney – 6th Cyclists Battalion, Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment. Died 19th May 1917.

Edwin Newland Finney lived at 78 Hamilton Road with his widowed mother and was a student teacher. He was commissioned into the Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment (Royal Canadians). He was serving with the 6th Cyclists’ Battalion and died on 19th May 1917, at the age of 22. The details surrounding his death are not clear as his battalion is not known to have been in France at this date. It is probable that he was seconded to another Regiment (Officers’ headstones bear the regiment into which they were commissioned, rather than that with which they were serving when killed). He is buried in the Point-Du-Jour Military Cemetery, Athies, Pas de Calais, which contains the remains of soldiers, from various Regiments, who died in the area between April and July 1917.

37606 Private E.A.J. White – 1/5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. Died 13th April 1918.

Edgar Arthur John White was conscripted at the age of 18 and lived at 34 Guest Road with his parents, he was their only son. He was drafted to the 1/5th Battalion, Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry which was the Pioneer Battalion (‘labourers’) of the 62nd (South Midland) Division. By March 1918, manpower prevented the manning of a continuous line of trenches, the front line instead being demarcated by a series of outposts. Defending ground north-west of St Quentin in March 1918, the 62nd Division and many others felt the full force of the ‘Kaisersschlacht’ – the German Army’s final gamble of an all-out assault on 21st March 1918. Driven back, in places as much as 40 miles, Edgar White’s unit found itself southeast of Ypres, where he was fatally wounded. In the prevailing confusion, his grave was lost. Edgar White is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial, Hainaut, Belgium. The Ploegsteert Memorial commemorates more than 11,000 servicemen who died in this sector during WWI and have no known grave. Most of those commemorated by the memorial did not die in major offensives, they were killed during the day-to-day trench warfare, which characterised this part of the line.

J11256 Able Seaman E.A. Cox – Royal Navy. Died 3rd July 1914.

Edward Alfred Cox was the brother of Reginald James Cox, who is also listed on Bishopstoke’s Roll of Honour to the fallen of WWI. Their parents lived in Weavills Farm Lane. Edward was born on the 8th of September 1894 and enrolled in the Royal Navy on the 6th February 1911, at the age of 17. He initially served on H.M.S Impregnable, a wooden hulled training ship, before being assigned to H.M.S. Blenheim, as a Painter Boy for a term of 12 years. On his personal details, it is recorded that on his right arm he had a tattoo of cross hands and a heart figurehead on a white ensign, whilst on his left arm he had a tattoo of a girl’s head. Establishing records for Edward Alfred Cox have been extremely challenging and it is thanks to the help of family members, who still live in Fair Oak, that details have finally emerged. According to the records of the Royal Navy Register of Seaman’s Services, 1900 – 1928, Edward Cox was serving on H.M.S Blenheim, a Blake class cruiser, built in 1890, which had joined the Mediterranean Fleet as a destroyer depot ship in May 1908. The ship was laying at anchor off Marmaris, Turkey on 3rd July 1914 when Edward was killed in a “boat accident”. Technically the declaration of war was not made between the United Kingdom and Germany until 4th August 1914, although the widely believed catalyst to the conflict, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, had taken place on the 28th of June 1914. Whilst the Royal Navy would have been on heightened alert, Edward’s death would not have qualified for his name to be recorded on a service memorial to honour the fallen of WWI. The Bishopstoke Memorial Committee clearly took a more pragmatic view and included his name alongside that of his brother Reginald. Our memorial is the only location where his name is remembered.

8115 Private F. South – 2nd Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 7th August 1915.

Frank South’s parents lived at 13 Guest Road. He had enlisted in the Hampshire Regiment as a Regular soldier in 1908, being drafted to the 2nd Battalion, serving in South Africa before a two-year posting to Mauritius. The Battalion was posted to Bombay in December 1913 and then stationed at Mhow, where it was when war was declared against Germany in August 1914. Having been relieved by the Regiment’s 7th Battalion, the 2nd Battalion returned to England to join the 88th Brigade of the 29th Division (later to be known as the ‘Immortal 29th’) who were destined to land from the converted collier, SS River Clyde, at ‘V’ Beach at Sedd el Bahr, on the Gallipoli Peninsula, on 25th April 1915. Within a fortnight of the landing, three quarters of the Battalion had become casualties. Successive attacks had been made on Turkish positions which culminated in an attack on the village of Krithia on the 6th of August. It may well be that Frank was one of the 210 wounded, in addition to the 242 killed and missing in this action. He was evacuated only to die at sea on 7th August 1915 at the age of 24. He is commemorated on the Helles Memorial that stands prominently on the Gallipoli Peninsula, Turkey.

352049 Battery Sergeant Major F.W. Hutchinson (MiD) 71st Heavy Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery. Died 30th November 1917.

Frederick Hutchinson was a pre-war Territorial who most likely served in No 1 Heavy Battery, Hampshire Royal Garrison Artillery and would have attended training in their Drill Hall, which was in Chamberlayne Road, Eastleigh. Frederick Hutchinson lived with his wife and young son at 29 Church Road, prior to WWI and worked as an electrician for the London and South Western Railway Company. Rising to the rank of Battery Sergeant Major (the senior Non-Commissioned Officer after the Officer of the unit), he served with 71st Heavy Battery, which had gone to France in February 1915. The 20th of November 1917 saw the employment of tanks en-masse, when over 400 machines made spectacular advances in an assault on the Hindenburg Line. The Germans were quick to bring up substantial reserves with which to mount a counterattack and re-took the majority of the ground taken in the initial British assault. Already Mentioned in Dispatches for gallant work, Battery Sergeant Major Hutchinson was killed by German counter-battery shellfire on 30th November 1917, aged 37. He is commemorated on the Cambrai Memorial at Louverval, France. His records show that his wife Gertrude was now living at 57 Church Road at the time of his death. A brass plaque bearing his name, along with the names of fellow villagers, the brothers Albert and Walter Webb, who died serving in Palestine, exists in the old Bishopstoke Reading Rooms in Church Road.

203732 Private F. Dann – 2/4th Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. Died 28th February 1917.

Frank Dann lived with his parents at 11 Montague Terrace according to the 1911 census and was employed as a blacksmith’s striker, probably with the railway. He was called up and drafted to the ‘Ox and Bucks’ 2/4th Battalion, forming part of 184 Brigade in 61st Division, which had recently taken over a sector of the front line near Ablaincourt, south-west of Peronne, from the French. In the fading light of the afternoon of 28th February 1917 preliminary German artillery fire, thickened by trench mortars and rifle grenades, descended on the trenches of the Battalion. This fire prefaced a strong German raiding party which inflicted considerable casualties of which Frank Dann was one. He died at the age of 32 and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, France. This memorial is dedicated to the Missing from the battles of the Somme. His casualty records indicate that he had married. His father and wife Ellen were listed as next of kin.

12370 Private F.H. Pitman – 9th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment. Died 19th April 1916.

Frank Henry Pitman lived with his parents at 18 Portal Road and volunteered to join the 9th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment in 1914. Frank went with his Battalion to Gallipoli, relieving 29th Division in Cape Helles, in July 1915 and later landing to take part in operations against Sari Bair. Evacuated from Gallipoli in January 1916, the 9th Royal Warwickshire Regiment landed in Mesopotamia, 13th Division being part of the force to relieve the besieged Kut-El-Amara. During these operations, Frank was wounded and died of his wounds on 19th April 1916 at the age of 23. He is commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq.

241607 Private G. Goddard (MM) – 2/5th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 20th November 1917.

George Goddard lived with his parents at 34 Spring Lane and volunteered to serve. After training, he was drafted to the 2/5th Battalion at Secunderabad in India. The Battalion formed part of 232nd Brigade in the 75th Division, which had been newly formed to reinforce the offensive against the Turks in Palestine. Reaching Suez in early April and after training and instruction from 163 Brigade, they took their place in the line south-west of Gaza at the end of June. D Company of the 2/5th Battalion, remained to support the Hampshire’s 8th (Isle of Wight Rifles) Battalion in what was known as the ‘Beach Post Raid’, which was regarded as the ‘Rifles’ finest trench raid of the war. On the night of 14/15th July 1917, a combined British force, some 200 strong, attacked a Turkish post with great success, killing and capturing over 100 Turks at a cost of one man killed, 2 missing and 10 wounded. Private Goddard assisted the raid commander, Lieutenant Brannon, in trying to bring in a wounded man and, for his part in the raid, George Goddard was awarded the Military Medal. In November, the Gaza – Beersheba line having been broken, the 2/5th Battalion were advancing on Jerusalem when, on the 20th November 1917, D Company sustained several casualties in recovering ground lost by another unit. George Goddard, at the age of 19, was one of these casualties. He is buried in the Jerusalem War Cemetery, Israel.

3/3282 Private H.A. Pragnell – 1st Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 27th April 1915.

Herbert Pragnell volunteered soon after war had been declared in August 1914. His parents lived at 79 Stoke Common Road. He was one of several hundred men drafted to the 1st Battalion, Hampshire Regiment, which by the end of 1914 had been reduced from over 1,000 men to 366 ‘originals’. The 1st Hampshire Regiment had seen action at Le Cateau. They were marched over 200 miles to reach what is now Disneyland Paris and from there marched north to the banks of the River Aisne. Moving to the Ypres sector by train in October 1914, the 1st Battalion had a relatively quiet 6 months in the Ploegsteert area, at the southern end of the Messines Ridge, running due south from Ypres. The use of gas by the Germans on the evening of 22nd April 1915 created a grey-green cloud that drifted across positions held by French Colonial troops, who broke ranks, abandoning their trenches and creating an 8,000-yard (7 km) gap in the allied line. However, the German infantry were also wary of the gas and, lacking reinforcements, failed to exploit the break before the line was reformed. Late on 25th April, the 1st Battalion Hampshire Regiment moved to plug part of the gap, north of the village of Zonnebeke. In the confused fighting of the next two days and under heavy shellfire preceding probing infantry attacks, the Battalion sustained 200 casualties, some buried in churned up ground, (a foretaste of the grimness of the conditions in the autumn of 1917 at the Battle of Passchendaele.) Herbert Pragnell was killed at the age of 23. He was one of some 54,896 names of the Missing who fell in the Ypres Salient before 17th August 1917. He is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium, which is inscribed: To the officers and men who fell in the Ypres Salient, but to whom the fortune of war denied the known and honoured burial given to their comrades.

33444 Private H.J. Pile – 11th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment. Died 30th March 1918.

Henry James Pile (not Pyle as inscribed on our Roll of Honour) was living with his parents at 2 Fair Oak Road in 1911 and working as a farm carter. Volunteering to enlist in the Hampshire Regiment in November 1915, he was drafted to the 11th Battalion, the Pioneer (labour) Battalion of the 16th (Irish) Division. As with many formations, this Division was caught in the ‘Kasiersschlacht’ of 21st March 1918. German troops, released from the Eastern Front, after the Russian Revolution of October 1917, mounted its ‘final throw of the dice’ offensive on the Western Front. With an original strength of some 17,000 men, the Division had been reduced to little more than 1,200 soldiers by the time that Henry Pile lost his life at the age of 27. Henry is commemorated on the Pozières Memorial, Somme, France, to the Missing of the 5th Army who lost their lives in the German Offensive of Spring 1918. According to his military records for next of kin, his parents had moved to 22 Nelson Road by 1918.